Stone Eel Traps in Susquehanna Could Be Older Than Egypt's Great Pyramids

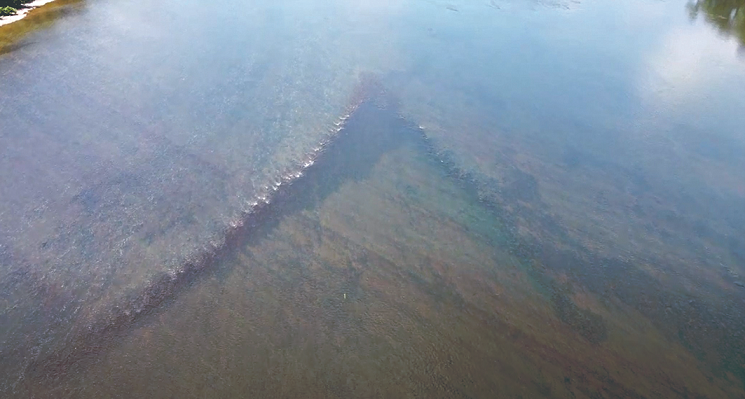

USA / AGILITYPR.NEWS / January 27, 2021 / As a kid growing up on Bald Top Mountain, with a birds-eye view of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, Van Wagner would look down during times of low water to see a mysterious “V” on the river bottom, pointing downstream.

Eventually he learned what it was — an old eel weir built from stacked river rocks, a simple but effective way to funnel and catch migrating American eels. As the eels swam downstream, the walls of the weir funneled them to a narrow point where they could be captured in traps or more easily speared.

Wagner, now an environmental science teacher at a high school near his hometown of Danville, PA, learned the story known and passed along by generations of local residents: The weir had been built by Native Americans. Indeed, it is located at the mouth of Mahoning Creek, where a community of Native Americans once lived.

Wagner’s own research led him to the startling possibility that this Native American artifact might have been built as much as 6,000 years ago — well before the oldest of the great pyramids of Egypt. He asserts this possibility because wood recovered from an old capture basket at the end of an eel weir in Maine was carbon-dated to an origin of roughly 4,000 B.C.

Moreover, it seems the Susquehanna is chock full of these ancient stone eel traps, underwater landmarks still standing after centuries, even millennia, of floods. The weir near Danville is about an eighth of a mile across at the open end of the V and its stone wall rises anywhere from 3 to 5 feet off the river bottom.

The historical record doesn’t offer much information on the number and whereabouts of other eel weirs in Pennsylvania, but satellite imagery has yielded some answers. When COVID-19 grounded field trips this year at Lewisburg Area High School, Wagner tasked his students with poring over satellite imagery of the Susquehanna to find the telltale Vs of eel weirs.

So far, they think they have found several dozen, almost all of them near documented Native American sites.

That’s no surprise to Aaron Henning, a fisheries biologist with the Susquehanna River Basin Commission. “There are hundreds out there. There’s one next to the airport in Harrisburg,” he said.

One simple reason may be that the snakelike fish were once a primary source of food for people living along the Susquehanna. “Native Americans used to smoke and dry the eel meat to be used all winter,” Wagner said. “This was likely the most important source of protein and calories for local people for several thousand years.”

Swatara Creek near Harrisburg draws its name from a Native American word believed to mean “where we feed on eels.” Swatara Township has an eel in its crest. The word “shamokin,” as in Shamokin PA, and a Susquehanna tributary of the same name, is said to mean “eel creek” in the language of the Delaware tribe.

According to the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission website, “Estimates of historical abundance suggest that eels made up 25% of all fish biomass in the Susquehanna River basin.”

Weirs also have been found elsewhere in the Bay watershed — in Maryland, New York and Delaware.

In his 1992 anthropology master’s thesis, “Prehistoric Fish Weirs in Eastern North America,” Allen Lutins of Binghamton, NY, wrote that eels and other fish played an important role in the diets of Native Americans along rivers and the Atlantic Coast before what is known as the Woodland Period, roughly 500 BC to AD 1100.

The reason: Catching fish required little effort and risk. And American eels were plentiful. Wagner marvels that Native Americans obviously knew the migrating patterns of eels, invisible though they are under water. They knew to employ their traps in the fall when adult eels migrated in mass numbers down the Susquehanna. What they didn’t know — and what nobody knew until a few decades ago — was that the eels they didn’t catch would end up as much as 1,000 miles away, in the Atlantic Ocean’s Sargasso Sea, where they would mate, spawn and die, or that their offspring would somehow find their way back to the very rivers and creeks where their parents had lived.

The eel is the Susquehanna’s only catadromous fish, meaning it is born at sea, spends its life in a river or estuary, then returns to the sea to spawn the next generation.

Anthropologist Lutins, citing other scholars, said it is often difficult to distinguish between prehistoric eel weirs and those built by early colonists who copied the Native American techniques. He cited several descriptions by settlers of stone or stake weirs in Virginia’s James and Shenandoah rivers still in use at the time by Native Americans.

Newly arrived colonists took over the weirs and built new ones. Eels became a diet staple of residents around Danville and remained so into the early 1900s, when hydroelectric dams started cropping up on the river, blocking the young eels’ return migration and short-circuiting the ancient reproduction cycle.

But the generations of eels already upstream continued to migrate every fall, when their time came. In September 1914, four years after the Holtwood Dam, downstream of Harrisburg, had blocked the returning juveniles in the spring, 3 tons of departing adult eels were taken in 10 days from the Danville weir, according to historical documents Wagner unearthed.

“The word spread quickly when the eels were starting downstream and men would leave their jobs to man their eel nets,” Wagner wrote. “Boys could be seen walking the streets of Danville with a stringer of eels thrown over their backs. They would stop at restaurants, bars and family homes to sell the delicacy to anxiously awaiting purchasers.”

Even after four more hydroelectric dams were built across the Susquehanna, catches of the dwindling adult population of adult eels — which can live up to 40 years and grow to 5 feet long — continued in the river into the 1950s.

In recent years, the federal government and fisheries agencies from Pennsylvania, New York and Maryland have stepped up efforts to restore the eel population. Since 2005, more than 1.5 million young eels that have made their way back from Sargasso Sea have been captured at the Conowingo Dam and trucked upriver for release.

Photo: A still photo taken from a drone video of an ancient stone eel weir in the Susquehanna River near Danville, about 60 miles upstream of Harrisburg. It is believed to have been built by Native Americans, possibly as far back as 4,000 B.C., based on carbon dating of surviving pieces of a wooden trap from a similar weir found in Maine. (Courtesy of Luke Wagner)

This article was originally published in the January 2021 issue of the Bay Journal and was distributed by the Bay Journal News Service.

Distributed free to news organizations and nonprofits by the Bay Journal News Service. © 2020 by Bay Journal Media.

Contacts